ODONATA AT REST

Nancy Au

Bernice Chan pumps her arms as she walks the thirty blocks from her home to Saint Gregory Middle School. Her short black hair bristles in the frigid January sun; her eyeglasses magnify her toffee-brown eyes. Bernice’s mind works like her mother’s, a part-time scientist who distributes medication at Golden Gate Senior Care Center. Like a scientist, Bernice uses all of her senses to observe four homeless men her father’s age: she notes the pungent odor of urine and liquor, and the fervent sounds of coins rattling in cups. The men count their earnings in public while slurping 7-11 Big Gulps and lamenting their blackened, frostbitten toes.

The men compliment Bernice’s green-checkered school uniform her mother had ironed that morning, pose interesting questions as she passes. With one man, Bernice hypothesizes that, yes, tortoises are slower than tarantulas. Bernice drops a coin in his coffee cup; the man recites a singsong blessing about a bum who can still chew gum. Bernice continues on to school, stops to laugh her machine gun heh-heh-heh at the faded poster of a blond woman eating a slice of pizza taped in the greasy window of Yum Yum Dim Sum.

Bernice’s laugh does not endear her to the nuns who run Saint Greg’s.

“Today,” says Ms. Adams, the school’s youngest nun, during first period, “I will teach you about the bears and the bees of sex because you never know what garbage you learn out there.” The young nun who teaches Bernice’s favorite subject, biology, sports a blue habit, vermillion pants, and white seashell earrings, and sits on the desktop the way teachers do in movies. “Remember the video about the pack of wild coyotes being born?”

Bernice remembers how her heart had pumped faster and faster as out of the coyote mother’s body seven glorious pups glided. Bernice had barely been able to keep her seat; she’d wanted to stand in ovation as the furless, pale wet pups, ears still slicked down, piled on top of each other in the dirt. What a miracle! What pure delight! Bernice had wanted to shout.

“Can you imagine the pain?” Ms. Adams asks the class. “Her body splitting open like that?” Ripples of uneasy giggles and murmurs fill the classroom. Bernice remembers the smells of her pet rabbit giving birth—salted, spongy, squid porridge, a murky morning mouth. She thinks of her mother’s skillful rabbit surgery, the ugly red smoothness of the blind kits, how her mother tried to warm life into the dying doe using a blanket nested inside of her own bed.

Bernice compares her mother’s swift-thinking agency at home and as a veterinary surgeon in China to the uninspired work at the senior center doling out heartburn medication. She thinks of how her mother hides her intelligence from her nosy manager, how she cries silently in the janitress’ closet after a sickly client dies—the tiny utilitarian room becoming a well-stocked cocoon for her tender heart.

Ms. Adams begins to draw on the board, images of reproductive organs and their corresponding names. The fallopian tubes connecting the uterus to the ovaries look like legs, and the one-dimensional line drawings of ovaries remind Bernice of wings. Bernice thinks of the tales of her mother’s birth, how she was born as a damselfly—how all of their Chinese ancestors could fly, but that here in America, they were members of a grounded flock.

Bernice has heard stories of her mother’s mutation for years. She often tries to imagine her mother as a damselfly nymph in China, her tender skin splitting across her back, long translucent wings unfurling, her first wobbly flight. And she imagines her mother’s mutation from Odonata into a wingless human, her engorged pregnant belly, wings shorn from her back to be burned along with her medical degrees, filling the house with an enchanted haze fueled by the greatest sacrifices her mother could give.

Bernice makes a sound like a trumpet exhaling. Ms. Adams claps her hands for attention, lands her gaze on Bernice who is anxious to get to lunch and then next period’s computer lab.

Pencils scratch away in notebooks, in what her mother calls ‘superbly coordinated handedness.’ On the chalkboard, Ms. Adams lists three tenets that are practically the school’s motto:

1. Take your time.

2. Don’t be boy crazy.

3. Don’t spend too much money on clothes.

“Are we clear?” Ms. Adams asks the room. “Understand?”

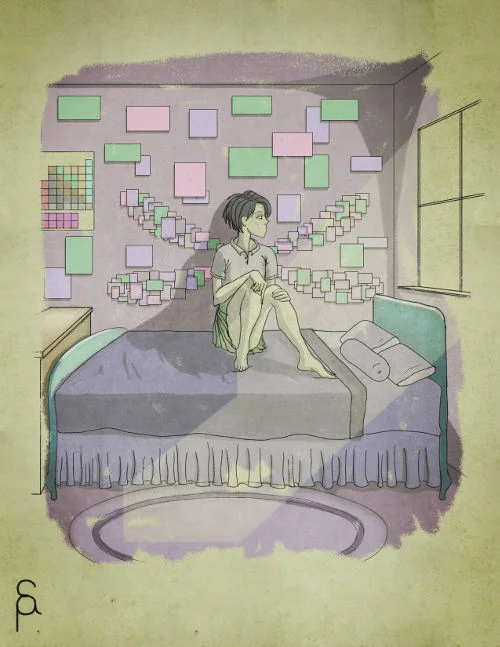

The other girls nod. But Bernice does not understand. This is not enough to understand. Her own bedroom walls are heavy with bright dream-filled art, the periodic table, and posters of Shirley Ann Jackson, Chien-Shiung Wu, and Rachel Carson.

As the other girls begin to rummage in their cubbies in search of sweaters and lunch bags, Bernice thinks of her mother’s bedtime stories describing the biochemistry and physiology of horses, speaking in Science which is the universal dialect of damselflies. She thinks of the tenets her mother had taught her; how sexiness is a state of mind, and it is a good mind that knows how to use it; most importantly, that Bernice existed because of biology, because different fleshy parts on her parents rubbed together to make sparks, and Bernice grew out of that light. How was biology not already a miracle?

Bernice raises her left hand and clears her throat like she has seen her mother do on the phone with their landlord when the rent was late.

“Yes, Bernice?” nods Ms. Adams.

“My mom says that if you don’t use it, you lose it. And it’s ‘the birds and the bees.’”

The sound of her classmates’ giggles follows Bernice and the nun out in to the hallway.

“You hardly speak up in class,” says Ms. Adams, “and then you say this? What’s going on inside that head of yours? Do you want to miss our next fieldtrip to the spider museum because of your attitude?”

Bernice smiles nervously and lets out a weak heh-heh.

Ms. Adams frowns. “You got into this school because you won a random district drawing. Do you think you deserve to be here?”

“Yes.”

“You’re just a kid. What do you know?”

Bernice wants to tell her exactly what she thinks about the inconvenient lottery that landed her in a private school over an hour from home, a school that taught that the Kraken was just a swollen octopus, that cannibals were just good at eating, that space travel and immigration were just symptoms of depraved curiosity. A school that promises ivory-glazed Ivy League futures for its students.

But Bernice just smiles at the nun.

“Well, I’m glad you’re getting such a kick out of this,” says Ms. Adams, her patience shrinking.

Bernice shifts from foot to foot as the nun decides what to do. Everyone knows that spiders’ webs wind around anything that stands still for long enough; flies that are not observant get caught in the sticky threads and die when the spiders return to drain their blood.

Bernice clicks and unclicks her dental retainer with the flat of her tongue as Ms. Adams calls a colleague for advice on the classroom’s beige telephone. On the phone, the nun nods and mm-hmmm’s, and says, “I keep getting these. Mm-hmmm. . .So true. . .I don’t know why!”

Ms. Adams’ decision is for Bernice to spend lunch break indoors with her. The nun sits cross-legged on her desk while she eats. She shapes curdles of mashed potatoes into God’s beard, pours on gravy black as coffee. God looks like he’s blistered in the sun because Ms. Adams uses crumbles of meatloaf for his face. Tangles of green arugula form his long disobedient hair. Bernice unwraps the large, soggy bamboo leaf from her tetrahedral-shaped jung. She nibbles sweet pork and sticky rice. She slurps her cranberry juice box through a straw, and chews on the tips of her disposable chopsticks while Ms. Adams flips through a fashion magazine.

Outside, Bernice’s classmates practice for their Presidential Fitness Award digital badges. From her desk, Bernice watches Grace, a new international student from Thailand, struggle to do a pull-up without her wings. The popular girls, eighth-grade basketball stars, can do all sorts of pull-ups for the President. Bernice watches as Grace dangles from the monkey bars until she slips off. Crack! Snap! Cry!

Bernice thinks back to second grade when she accidentally threw out her retainer with her lunch bag, then sat on her glasses, then her father died, then she refused to leave her bedroom for six weeks, then sat on gum, then the senior center manager told her mother that asking for a raise and mentioning her veterinary surgeon degree was ‘just showing off when you can’t even speak perfect English,’ then a seagull pooped on Bernice’s jean jacket and her glasses, then she burned her mouth with green chili paste, then tasted her mother’s science for the first time, which gave her a new language to speak her grief in.

“I dropped out of college to become a photographer for Vogue. Did you know that?” Ms. Adams uses her fork to point at Bernice, who shakes her head and listens in fascination for the first time since the coyote video.

“I owned expensive cameras. I learned how to outfox bosses, convinced them to hire me over the photographers who’d been there longer. They all begged for my friendship. I worried sometimes that I was building an empire of featureless friendships, like a queen bee and her hive of drones. I had two boyfriends at any one time: one Asian, one rich. I flew all over the world. I was everywhere all of the time, for everyone. I was the opposite of repulsive; I was a magnet.”

“How could you give it all up?” Bernice cries out. “Why are you here?”

Ms. Adams shrugs and tosses her holy meatloaf in the trash.

“I was like you. Independent. Young. Craving. . .everything. But one day on a photo shoot in Seattle, I just didn’t want it anymore.”

“What, it?”

“Everything.”

“But this is death!” Bernice imagines an Odonata shedding her shimmering veined wings to become a gloomful human mother with her stolen visits to the custodian’s closet.

Ms. Adams stretches out her legs, studies her sturdy leather sandals and flat toenails. “Come, it is almost time for your next class. Clean up. You can go.”

“But—!” Bernice throws her arms in the air for emphasis.

Ms. Adams slips from her perch on the desk, takes a step towards Bernice, rests her hand on the girl’s shoulder. “Don’t you know what it is that we are trying to teach you?”

“I know.”

“What do you know?” The nun’s hand drops to her side. “You think that either the world is against you, or that you are the world. Is that right?”

Bernice searches outside the window for her answer. Her classmates play monkey tag on the bars, untrammeled by their full bellies or blistered palms, kicking at each other and howling.

“Out there, there is death. There is disease. But, there is also God’s love, and there is choice. You can be anything you want to be,” says Ms. Adams.

“Mom says the only thing everyone has is…we all die. It’s what we do.”

“How do you love?”

“We have Science.”

“What does science tell you about love?”

Bernice tries to imagine what her mother would say at home, when she is full of agency and spark, when she rattles off recipes in Chinese, when she recites the periodic table from memory (including the newest elements!) using her specialized Chinese scientific-speak. She imagines the damselfly in free flight, its rapid aerodynamics, its powerful wingbeat, clap and fling. She imagines a swaying willow branch, and the damselfly’s slender perch, holding its wings over its body at rest.

Bernice takes a deep breath. “Mom says there are many loves in the world, and the lovers who can’t leave them—mushroom lovers, confetti lovers, gin lovers, cheese lovers. Mom says death is evolution. I am evolving. Mom says that we don’t all get choices. That when we lost our wings… that… erm… Odonata have,” she stutters. “Mom says—”

“I am telling you.” Ms. Adams hands Bernice her backpack. “Life here can be shining and glamorous. And maybe it’s just not for everyone. Just tell your mom that I said so. Tell her that.”

Outside in the air, swinging under bars, Bernice’s classmates walk hand over hand, back and forth, side to side, spinning on their own axes. But Grace climbs another structure, a glinting geodesic dome: hard plastic, new metal, copper pipe, wood, rope. She reaches the top, lays down on the shape.

Bernice’s steps out of the classroom drag into the hallway. They continue to drag on her trek home after school. The straps of her black nylon Jansport backpack dangle off her hips like a lazy sea creature. At the first red light, a nearby bus gives a tired tssss as it kneels to release three passengers, two old and one white. There are no homeless to observe. She uses a black marker and drags a line along a gray and worried abandoned building. At the second red light, Bernice catches up with a woman who from behind resembles her mother, but for a large dark mole on her neck.

As they wait for the light to change, the woman folds her hands before her as if in lazy prayer, and Bernice wonders if Ms. Adams’ god can see the emptiness in the gesture. Bernice arranges her feet so that they line up with the woman’s. They stand side-by-side, alone together, equals for thirty red seconds. Cars rush by, and the passing wind picks up Bernice’s backpack straps so they tremble like black wings.

NANCY AU's stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Foglifter, SmokeLong Quarterly, The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, Necessary Fiction, Fiction Southeast, Word Riot, Identity Theory, Prick of the Spindle, and elsewhere. She was awarded the Spring Creek Project collaborative residency (Oregon State University), which is dedicated to artists and writers whose work is inspired by nature and science. She graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in Anthropology, and is an MFA candidate at San Francisco State University where she taught creative writing. She teaches at California State University Stanislaus. And is the co-founder and instructor at The Escapery, a writing unschool.